ReCOVERed Art – Descriptions

1. Perhaps one of the nastiest names nameable in the world of contemporary art crime is Subhash Kapoor. For many decades Kapoor dominated the trade in Indian antiquities—so much so that the MET, upon receiving a sizeable donation from the dealer, even graced him with a special honor. Kapoor, who was arrested in 2011 at a Frankfurt airport and later extradited to Chennai, India in July 2012, has faced charges for accepting plundered artifacts and antiquities stolen from all across Asia. Kapoor, once referred to as “the man who sold the world,” had been operating primarily out of the city of New York prior to his arrest. When authorities raided his storage facilities and warehouses they seized a total of 2,622 objects valued at over $100 million, many of which had been illicitly looted from sacred sites in India, Cambodia, and Afghanistan among other countries.

Two of the more famous illicitly trafficked objects which passed through Kapoor’s hands during his lengthy career are the $5 million Dancing Shiva, a 10th century bronze Buddha from Thailand, and this statue of Saint Manikkavachakar, a Hindu poet and mystic.

2. Paul Cézanne’s Boy in the Red Vest is just one rendition in a series of four oil portraits that depict a young male sitter. What is special, I ask you, about this particular iteration of the series? Is it the rich red, white, and blue hues that color the painting? Is it the melancholic affect that the boy broodingly emanates? Could it be Cézanne’s figuring of the boy’s pose, or the vantage point from which he captures his subject?

If you cobbled up any of these guesses from those listed above, well, it’s possible that you’re not wrong! However, none of these responses fit the answer we are looking for. What is especially unique to this painting is that the work, part of the Foundation E.G. Bührle in Switzerland, was stolen from the museum’s collection in 2008. For years, authorities relentlessly sought the valuable painting which is, in fact, the museum’s most valuable asset. It was not until 2012 that the Cézanne, valued at $91 million, was recovered in Serbia and returned to the collection.

3. Horrific looting took place at the Baghdad Museum in April 2003. As of June 2005 some 15,000 items had been reported as st olen, including 4,800 cylinder seals, some dating as far back as 2300 B.C.E. In 2004, the FBI established a specialArt Crime team in specific response to the series of thefts that had devastated the Iraqi museum. Bonnie Magness-Gardiner, the primary supervisor of the program, has commented on the decision to set up the FBI Art Crime team: “We realized then that we needed a group of agents who were specially trained in the area of stolen and looted art.” In November 2013 during a private ceremony in held at the Embassy of Iraq in Washington, D.C., the FBI repatriated four missing cylinder seals to the Iraqi government. Rolled across wax or soft clay that later hardened, cylinder seals like these form an imprint or “signature”. This imprint was used to mark property or document ownership.

olen, including 4,800 cylinder seals, some dating as far back as 2300 B.C.E. In 2004, the FBI established a specialArt Crime team in specific response to the series of thefts that had devastated the Iraqi museum. Bonnie Magness-Gardiner, the primary supervisor of the program, has commented on the decision to set up the FBI Art Crime team: “We realized then that we needed a group of agents who were specially trained in the area of stolen and looted art.” In November 2013 during a private ceremony in held at the Embassy of Iraq in Washington, D.C., the FBI repatriated four missing cylinder seals to the Iraqi government. Rolled across wax or soft clay that later hardened, cylinder seals like these form an imprint or “signature”. This imprint was used to mark property or document ownership.

4. With legs comfortably crossed and a fan clutched in one hand, Matisse’s “Femme Assise” or “Seated Woman/Woman Sitting” shows little sign of movement. Our enthroned subject, however, has not remained as motionless as her pose might promise. She has travelled more than many.

During the second World War, Nazi authorities set their eyes on the art collection of Paul Rosenberg, a prominent Jewish art connoisseur, best known for his role in promoting early modern painters. Many of these artists iconic works ended up in Rosenberg’s influential gallery at 21 Rue de la Boétie. As an artistic hub for some of the most significant French modern artists, Rosenberg’s taste in art was outstanding and contained works of art by Géricault, Courbet, Monet, Manet, Degas, Renoir, Toulouse Lautrec, Picasso and Matisse.

Forced to quickly abandon his formidable collection and thriving business in 1940, Rosenberg left many pieces of his collection in Paris, 75 paintings in Floirac and a staggering 162 artworks in a in a bank vault in Libourne, near Bordeaux. It was here that he had stored Matisse’s lovely lady.

Seized in Libourne in 1941, the painting then passed through the hands of Gustav Rochlitz in Paris and later on to Hildebrand Gurlitt, told allied authorities after the war that his collection had been incinerated in the fire-bombing of Dresden.

Then, in 2010, another story of transit summoned the Seated Women from her 75 years of stasis. Cornelius Gurlitt, Hildebrand ‘s aging son, was travelling from Zurich to Munich when authorities found a suspiciously large amount of cash on his person. Suspected of tax evasion, authorities conducted a search of Gurlitt’s apartment and discovered a substantial trove of stolen and unprovenanced works: paintings by Picasso, Chagall, Courbet, Renoir, and, importantly, Matisse’s Seated Women. In May 2015, the painting was returned to Paul Rosenberg’s heirs.

Considered the greatest art theft in history, more that 650,000 works of art were confiscated from Europe by the Third Reich during the Second World War, many have never been recovered.

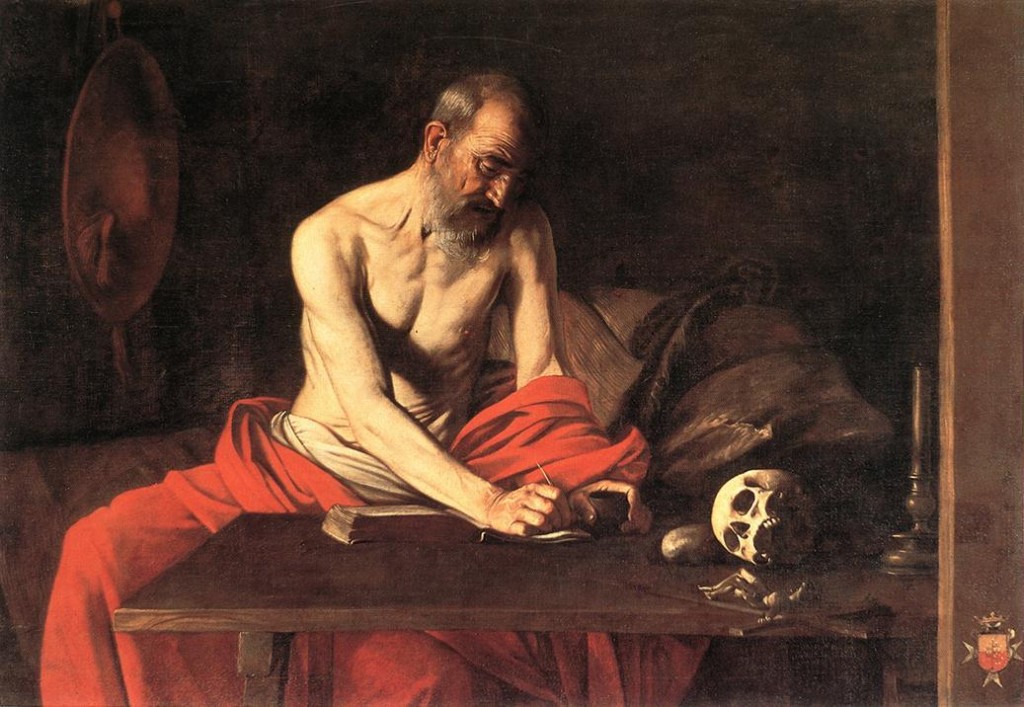

5. It has been alleged for centuries that Caravaggio, following a vicious dispute over a tennis match, murdered Ranuccio Tomassoni in 1606. What Caravaggio’s earliest accusers probably could not have predicted was that so much other criminal activity would come to be associated with the Baroque painter’s professional work. Caravaggio’s paintings have been at the center of some major forgery cases. Even more dramatic than these incidents are the art heists to which Caravaggio’s work have been subject.

Father Zerafa, a Dominican priest and the former Curator and Director of the Malta Museums spent a year working out negotiations with a group of thieves who had stolen this Caravaggio painting of St. Jerome. Zerafa’s diplomacy worked quite successfully and the museum recovered its prized Caravaggio, though not without some collateral wear and tear. Zerafa, commenting in his book, The Caravaggio Diaries, observes: “at times it was easier to deal with the Mafia than with Ministers and Monsignori.”

6. One of the more unsettling episodes of art theft as of late is that of the Castelvecchio Museum in Verona. On November 15, 2015, three robbers broke into the small, regional museum and stole 17 paintings worth an estimated €15 million. Many of these precious masterpieces were painted by major early modern painters such as Rubens, Bellini, and Tintoretto among others. Police in Moldova and Italy arrested 13 suspects back in March and recovered all 17 works of art in the Ukraine.

This work, La Madonna della Quaglia, is widely attributed to Pisanello and epitomizes many of the aesthetic currents typical of the International Gothic style. The glimmering, gilded backdrop and the lush rose garden in which the Madonna kneels is the perfect marriage, in my mind, of Klimt’s sensuous, gold textures and Botticellian vegetation.

7. Whenever an unnamable wealthy Swiss collector purportedly consigns a precious and pricey cultural object to a major auction house, followers of art crime tend to receive this sort of anonymous owner information with raised eyebrows and suspicion. So it wasn’t a surprise that when Christie’s listed this first century A.D. Roman bust on their sales catalogue with a provenance of “private collection, Switzerland,” that London-based Libyan archaeologist Hafed Walda responded in disbelief. And rightfully so.

This work of Flavia Domitilla Minor was excavated with the rest of her body from Sabratha, a UNESCO World Heritage site in northwestern Libya. Domitilla’s head had once been on display in Sabratha’s Roman museum—in its rightful place, atop her stone body—until thieves decapitated the sculpture and ran off with the then head, now-bust.

Walda’s and other art scholars concerns over the object were dismissed by representatives of Christie’s and the piece was sold to an Italian buyer for £91,250 ($142,000). The Italian owner was made to voluntarily relinquish the bust when the Carabinieri Art Squad intervened and Domatilla’s head was eventually reunited with her body back in Libya.

8. Douglas Latchford, a self-described “adventurer-scholar,” purchased this 10th century Khmer warrior at a Sotheby’s auction. The Bangkok-based collector had already bought the Khmer warrior’s sibling statue, another 10th century work, which had been ostensibly looted from a temple in Cambodia’s northern jungles. When questioned about his acquisition of the kneeling warrior Latchford claimed he had purchased it in good faith.

Federal prosecutors, however, investigated the case further and later learned that Latchford had collaborated with another auction house to concoct false export permits for the statues. In May 2013 The Metropolitan Museum returned this and the second of the 10th century Koh Ker “Kneeling Attendants” looted from the Prasat Chen Temple at Koh Ker. They had been displayed as part of the Met’s permanent collection for almost 20 years.

Since 2013, six of the stolen statues from the Cambodian Koh Ker temple complex have been repatriated. Four more statues from the Prasat Chen temple are still believed to be held in private collections.

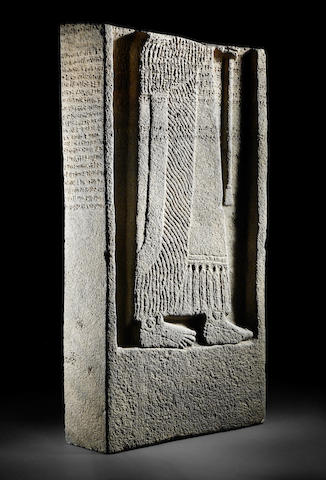

9. Some say that all publicity is good publicity, but when an auction house is accused of trading in illicitly looted antiquities it is not always the case. Like the time that the London-based Bonham’s tried to sell the lower half of this ancient black basalt stela from Dur-Katlimmu, (modern Tell Sheikh Hamad), of Assyrian King Adad-nerari III who ruled Syria some 2,800 years ago.

The auction house stirred up a media frenzy after it announced that the ancient stone block, which comprises just the lower half of this stela, (the top, with the head of the king was sold to the British Museum in 1881) would be up for grabs at its major Spring auction back in 2014. The piece had been listed as “Private collection, Geneva, Switzerland, given as a gift from father to son in the 1960s.”

After receiving significant pressure about the contradictory origin of the piece, most notably from the Saade Institute for Culture, Bonham’s withdrew the object from its intended auction. Interestingly, some of the cuneiform writing on the tablet is said to condemn anyone who moves the sculpture from its original, in situ location. So now I ask you, what’s worse: bad publicity from contemporary media or condemnation from ancient media?

10. It seems that Geneva Free Port is starting to face the kind inspective scrutiny that the storage facility should have been receiving for decades. The New York Times recently published an article on the complex that describes both the shady figures who rent out spaces at the Free Port as well as some of the illicit objects that sometimes populate its storage facilities.

This Etruscan sarcophagus was discovered in one of Geneva Free Port’s warehouses in 2014 along with forty-five crates containing a trove of Roman and Etruscan antiquities once belonging to Robin Symes, the disgraced British art dealer known to have trafficked illicit works of ancient art.

Syme’s trove of illicit antiquities had languished in the Geneva vault for more than 15 years, kept in boxes which detailed the contents as being owned by an off-shore company. It is believed that this was looted from a tomb in Tarquinia, one of the great Etruscan cities 50 miles north-west of Rome.